The December 1927 nor’easter was a massive storm. At sea, the National Weather Service issued an advisory blanketing the entire state of North Carolina and prompting an Atlantic storm warning from Norfolk, Virginia, to Wilmington, North Carolina, on December 1.

On land, newspapers reported at least four people froze to death in the storm as sleet and snow blanketed the state.

But the real horror was at sea, where two ships ran aground off the Outer Banks, and if not for the extraordinary resourcefulness and bravery of the Coast Guardsmen, the loss of life would have been horrific.

As it was, four crewmen of the Greek flagged Kyzikes (also spelled Kyzikos) were swept off the ship as waves battered the ship.

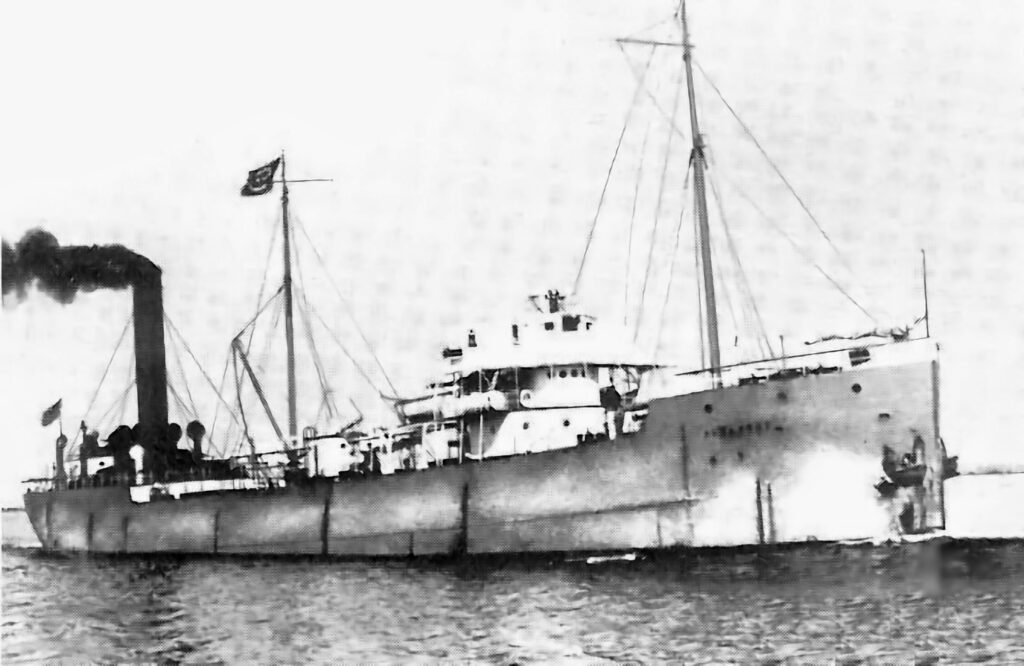

The Kyzikes

By 1927, the Kyzikes was an aging ship of little use to Sun Oil Company, which sold the vessel to the Greek shipping firm Costi Xydia and Sons. Launched in 1900 as the SS Paraguay, the ship spent two years carrying ore across the Great Lakes before being bought by Sun Oil and converted to the company’s first oil tanker.

For the next 20 plus years, the ship made regular trips between West Texas and Marcus Hook, Pennsylvania, carrying crude oil. But by 1927, technology had bypassed the Paraguay and Sun Oil sold the aging tanker to Costi Xydia.

The sale of the ship was approved by the United States Shipping Board with the stipulation that the ship would not make port at any US location.

On November 28, with Captain Nickolas Kantanlos in command, the Kyzikes left Baltimore bound for Seville, Spain, with a full load of crude oil.

Almost immediately, it was apparent that the Kyzikes was barely seaworthy. The ship began leaking badly, and Captain Kantanlos headed back to Baltimore to effect repairs. On November 30, the ship was again at sea, and the following day, December 1, as the Kyzikes steamed south, the seas were rising, the wind was steadily increasing, and the ship again began to leak.

According to the article Archaeological Investigation of the S.S. Kyzikos and the S.S. Paraguay written for the ECU Maritime History and Nautical Archaeology magazine Stem to Stern by Wendy Cole, Captain Kantanlos seemed to be aware of the National Weather Service warning but “decided to race the storm for Cape Hatteras where he would turn due East and head for Spain.”

However, Cole wrote, “the Captain misjudged the speed and intensity of the storm and instead of sailing in calm waters toward his home port in the Mediterranean, he was now desperately trying to keep his ship afloat.”

The crew attempted to pump water out of the ship, but it was leaking too badly, and at 4:30 p.m. on December 3, the captain ordered a distress call.

“Leaking fore and aft badly. In need of assistance. Position latitude 36-35 north, longitude 75-50 west. Unless you get to us quickly we may not be here. We tried to steer westward but drifting southward. Heavy seas running.”

That location placed the Kyzikes about 30 miles due west of Kill Devil Hills.

Knowing the desperation of the Kyzikes, five ships braved the heavy seas in a vain attempt to reach the vessel. The Coast Guard Cutter Carrabassett, based in Norfolk, joined the search. The Coast Guard cutter, though, could offer little help according to a December 4 New York Times article.

“The Coast Guard Cutter Carra Basset (sic), the largest vessel of that service in the region, reported that she was having great difficulty in making headway to the tanker from (Norfolk),” the Times reported.

On the foundering ship conditions were worsening.

Soon after the transmission a huge wave struck the ship taking four crewmen with it and crushing the lifeboats. Another wave tore the radio antenna from its mooring, leaving the Kyzikes with no means to broadcast their position. Surging seas extinguished the boiler, leaving the ship without power and unable to steer. Without the boiler for power, the ship’s lights were extinguished, making it all but impossible for rescue craft to see it at night.

The freighter City of Atlanta was close to the area and kept broadcasting an SOS, but the stricken ship was drifting at the mercy of the wind and waves. The British steamer Baron Harries reached the last reported location of the Kyzikes, but the ship had drifted far to the southwest by that time.

Early in the morning of December 4, the ship grounded off Kill Devil Hills, the stern of the ship striking the sandbar first. The force of the grounding was so great that the ship broke in two, the bow breaking off and coming parallel to the stern.

Crewmen on the stern saw lights through the mirk and thought they would soon be rescued, but the lights were the flashlights of the Kyziskes crewmen trapped on the bow. Realizing the bow was floating free and moving to shore, a gangplank was lowered and the crew united on the bow, according to Cole.

In the early morning light, Coast Guard Surfman Jep Harris from the Kill Devil Hills station saw the form of the ship’s bow and signaled help was on the way.

Although the Kyziskes ran around close to the Kill Devil Hills station, Coast Guardsmen from Kitty Hawk and Nags Head assisted in the rescue. Reports include a note that off duty surfmen from Caffey’s Inlet on the north end of Duck were also on hand.

Attempts to launch a rescue craft in the heavy sea were unsuccessful and a Lyle gun was brought into action. A mortar shaped cannon, the Lyle gun fired a shot with a line attached to it that would be secured on the ship. Crewmen were brought to shore in breeches buoys.

By 7:00 p.m., the 24 surviving crewmen of the Kyziskes were ashore and safe.

The Grounding of the Cibao, bananas and rum

Even as the men of the Kyziskes were being rescued, Coast Guardsmen of Hatteras and Creek Hill Stations were battling the surf, desperate to save the crew of the Norwegian flagged freighter Cibao, trapped in the shallow waters of Diamond Shoals.

The December 5 New York Times article recounting the rescue of the crews of the two ships that night, minced no words in describing how harrowing the rescue of the Cibao crew was.

“The rescue of the crew of the Cibao was far more thrilling, for the twenty-four men were dragged through a raging surf from the ship to the shore at the ends of ropes,” the paper reported.

The Cibao was a relatively small freighter, just 694 tons, and was heading north from Jamaica, its holds filled with bananas. With sustained winds reported to be 70 miles per hour, the wind, waves, and current overwhelmed the ship.

“It was 4 o’clock in the morning when we struck the beach,” First Officer Orum of the Cibao told the Virginia Chronicle for the paper’s December 12, 1927 edition. “We had been battling the storm for many hours. We were probably 100 miles below Hatteras when the gale came upon us, and from that time until we struck the ship was practically at its mercy.”

Hard aground at Diamond Shoals, the crew waited for daylight, hoping as the day lightened they would be seen.

“It was 7 o’clock or perhaps a little sooner…Then we could see the shore. We were stranded about four miles from the beach. We saw the signals of the life savers and we knew they would come to us,” the captain said.

The Coastguardsmen were able to bring their motorboats alongside the Cibao, but the fore of the waves were so great that the boats were in danger of being crushed against the side of the freighter. Desperate to save the crew, the rescuers told the crewmen to tie a rope around their bodies and lower themselves to the raging sea.

One by one, they came down and were then lashed to the side of the motor boats and brought to shore through the raging seas. At least one of the boats had to make a second trip to the grounded vessel, with Captain Mejlanders, master of the vessel, the last to leave. The Associated Press reported “several (rescued crewmen) were unconscious when pulled out of the surf…” with the New York Times writing, “eight of the men were unconscious or partly so when they were landed on the beach.”

The Cibao, however, was not a loss. Although grounded, it was relatively undamaged. Its cargo of bananas was certainly lost, and the fruit was jettisoned to refloat the ship. There are unconfirmed stories of children on Ocracoke and Hatteras Village eating bananas until they were sick.

The ship was towed to New York for repairs.

The Stories Do Not Quite End Here

The heroics of the Coast Guard crews were recognized beyond the borders of the United States. The Elizabeth City Independent in a May 3, 1929 article reported, “The Greek Government has conferred its Naval Medal for the rescuing of human lives on W. H. Lewark, officer in charge of the Kill Devil Hills Coast Guard Station, S D. Guard, officer in charge of the Kitty Hawk station and Walter G. Etheridge, officer in charge of the Nags Head station” for their actions rescuing the crew of the Kysikes.

The article also noted, “The Government of Norway presented similar medals to other Coast Guard men in January in recognition of the saving of the lives of the crew of the Norwegian steamer Cibao…”

Bananas, as it turns out, were not the only cargo in the Cibao’s hold. The ship was also transporting “21 cases of choice liquor” the Elizabeth City Independent reported.

1927 was the height of Prohibition, and the 21 cases of choice liquor had been consigned to the ship by the Bolivian embassy in Washington, DC. International law was clear on the subject—within the embassy, the laws of Bolivia were in effect, and Bolivia had no rules against liquor consumption.

“And so when the liquor was taken over by the Government, the Government had the responsibility of seeing that it got safely to its rightful owners. Uncle Sam had to deliver the goods,” the Independent reported.

There is another twist to the story of the Kyziskes.

In 1929, the US Army sent six of its Keystone bombers to use the Kyziskes for target practice. Dropping bombs from various heights, the bombing run was considered a success.

Later that same year, the Swedish flagged ship Carl Gerhard ran aground in exactly the same location. The Gerhard had been battling storms and heavy seas for eight days after leaving Halifax, Nova Scotia in early September.

Off the coast of New England, the weather deteriorated. At a time before any modern navigation aids, after eight days of being battered by waves, howling winds and overcast skies, the ship’s captain A. Ohlsson had no idea he was off the coast of the Outer Banks until he ran ashore at Kill Devil Hills.

Blown by the winds, the ship ran aground off Kill Devil Hills, slicing what was left of the Kyziskes in half.

The two ships now lie a few hundred yards off the Kill Devil Hills beach and are known as the Triangle Shipwrecks, a popular diving site.