November 30, 1879 was a clear night on the Outer Banks, although the breeze was stiff and the surf high. Why the schooner M&E Henderson ran aground at the north point of New Inlet just three miles south of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station will never be known. But the ship did run aground. Three crewmen managed to swim ashore; the captain and three other crewmen lost their lives.

The sinking of a ship and the loss of life were tragic, but compared to so many other disasters that have occurred along the Outer Banks, it hardly seems significant. Yet the sinking of that ship, largely forgotten by history, set in motion a series of events that had huge implications.

The Lifesaving Service published an annual report detailing personnel issues, expenditures, and needs. The report also contained particularly noteworthy actions by its personnel and the wreck of the M&E Henderson made the cut in the fiscal year 1879 report.

“It appears from the evidence taken, that…patrolman (Leonidas) Tillett, who had the morning watch on the beat south, returned to the house a few minutes after five o’clock in the morning, lit a fire in the stove and called the cook, then went upstairs, and looking with the marine glass from the south window, perceived, at some distance in the clear moonlight…a man whom he at first thought was a fisherman.”

Tillett, an experienced surfman, though, noticed that the man was not wearing a hat and surmised “… that he might have been washed ashore from a wreck.”

He immediately began walking south to meet the man and “…soon came up to a haggard and dripping figure, a sailor, tottering along very much exhausted, and only able to feebly articulate, ‘captain drowned—masts gone.’”

Two other sailors, weak and almost drowned were also found, but the captain and the other three crewmen had perished.

It was a great story and spoke highly of the professionalism and skill of the Lifesaving Service personnel at the Pea Island Lifesaving Station.

However, with the exception of the three survivors of the shipwreck, almost everything that Station Keeper George Daniels wrote and was used in the year-end book was a lie.

It began to unravel fairly quickly, and it was the three survivors who started the ball rolling.

It is unclear what their nationality was for it was reported that they spoke broken English. But one thing the three of them were clear about—Surfman Tillett did not meet them on the beach and that they walked to the Lifesaving station with no help from anyone.

The General Superintendent of the nascent Lifesaving Service was determined to make the service a highly competent, professional organization. The testimony of the three men called out to be examined and he sent Lieutenant Charles Shoemaker to investigate.

Shoemaker had no problem finding inconsistencies in Daniels’ report.

November 30 was a clear night. A shipwreck creates a tremendous amount of debris, and there was no explanation about why a supposedly experienced Surfman Tillett would not have seen the debris on a clear night during his patrol.

That discovery led to another problem. Keeper Daniels had clearly lied in his report to protect Tillett, and that was unacceptable.

Shoemaker, in his report, did more than point to the duplicity of Daniels and Tillett. He found that at least one of the crew at the station, Charles Midgett, was incapable of performing the duties of a Surfman and that the crew at the station was in general poorly trained and ill-prepared to render assistance to ship in distress.

There’s more—he also found that Keeper Daniels would frequently be absent to go “fire-lighting,” or hunting waterfowl at night.

With Shoemaker’s report in hand, Kimball authorized the court-martial and firing of the entire Pea Island crew, which allowed him to follow the recommendations of Shoemaker and another inspector, Lieutenant Frank Newcomb, both of whom recommended Surfman #6, the lowest rank, at the Bodie Island Lifesaving Station for promotion to Station Keeper. Surfman #6 was Richard Etheridge, a Black man, and former slave.

Surfman #6 was the only rank African-Americans were allowed to hold at Lifesaving Stations at that time, but Kimball’s inspectors were adamant that Etheridge was the best man for the job.

Shoemaker and Newcomb wrote separate recommendations for Etheridge, with Newcomb noting, “Richard Etheridge is 38 years of age, has the reputation of being as good a surfman as there is on the coast, black or white, can read and write intelligently, and bears a good name as a man among the men with whom he has associated during his life.”

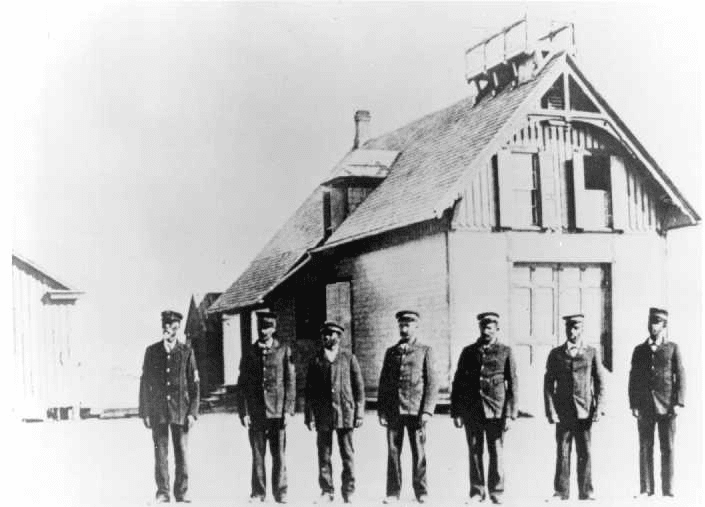

On February 1, 1880 Richard Etheridge became Keeper Richard Kimball of the Pea Island Lifesaving Station. No white man would serve with him, so the best of the Black surfmen #6 became the crew of the station.

By all accounts Etheridge was a stickler for detail, adhering to regulations and constant drilling. It all paid off on the night of October 11, 1896, the rescue of the ES Newman, still considered one of the most extraordinary rescues in Coast Guard history.

The US Lifesaving Service was the predecessor to the US Coast Guard, becoming part of the Coast Guard in 1915.

The Pea Island Lifesaving Station continued to be manned by an all-Black crew until it was decommissioned by the Coast Guard in 1947.